Discover Soweto

Soweto is a city within a city and home to more than 1.5 million South Africans. Once referred to as a ‘township’, it is now a thriving cosmopolitan urban centre that has risen from the ashes of South Africa’s apartheid era.

Located southwest of Johannesburg – South Africa’s economic capital city – Soweto boasts world-class infrastructure and rich historical heritage. A tour to Soweto provides visitors with a glimpse into the country’s tumultuous past and the essence of its modern-day multi-cultural diversity.

Sprawling low-cost housing settlements border the fringes of first-world developments. Authentic taverns serving traditional African dishes exist alongside smart restaurants that cater to the finest tastes. Hawkers earning a subsistence living selling their wares on the hot, dusty streets stand out in stark contrast to shop owners in the upmarket shopping malls.

Soweto is a city of many facets and beats to its own rhythm.

HOW SOWETO GOT ITS NAME

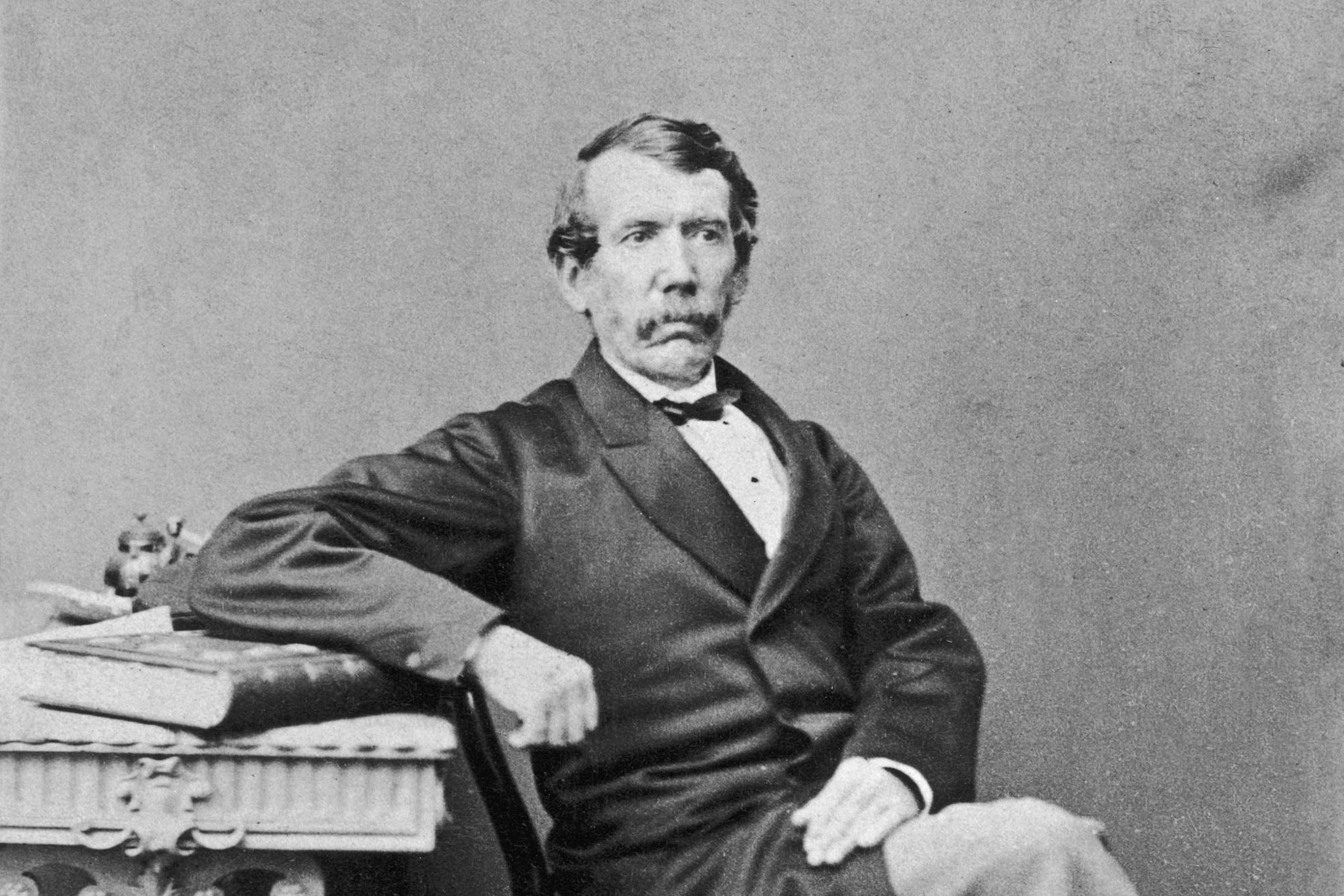

William Carr was chair of what was known then as Non-European Affairs. In 1959, he initiated a competition that required people to come up with a name for the collection of Black townships in the south-west of Johannesburg. The City Council settled on the acronym SOWETO, standing for South West Townships. The grouping of townships was officially recognised as Soweto in 1963.

RISING FROM THE ASHES OF APARTHEID

The National Party won the general election in 1948 and formed a new government. The party drove a harsh policy called apartheid, which is the Afrikaans world meaning ‘separateness’. The party governed South Africa with the intent of keeping the majority Black population separated from the minority White, and specifically Afrikaans, population.

The Johannesburg City Council did not support the National Party and competed with central government to control the Black townships of Johannesburg.

Johannesburg experienced a population boom in the late 1880s during the gold mining era when migrant labour descended on the region in search of work at the gold mines. Hostels and other accommodation were set up in the outskirts of Johannesburg for the growing Black migrant workers.

The sprawling informal settlements grew under apartheid rule in the 1930s. The National government forced Blacks to move out of Johannesburg to a so-called cordon sanitaire (or sanitary corridor), effectively separating Black communities from the White suburbs. The sanitary corridor was usually separated from White suburbs by a river, railway track, industrial area or a highway. This was the era of the infamous ‘Urban Areas Act’ of 1923.

At the time, residents of the townships (that would become Soweto) were only awarded temporary residential status and were regarded purely as a workforce for Johannesburg. For many years Soweto was the centre of violence and turmoil as its people struggled against the constraints of the segregation system and apartheid regime.

The former National government used these basic townships as a dumping ground for Black citizens and largely ignored them. The dusty roads were unpaved and the environment was stark and barren with no trees planted or green common areas. The shanty houses were a mix of iron, wood and brick; blazing hot to live in during the hot summer months and freezing cold in the icy winters.

Soweto was located far from the peoples’ workplaces and residents had to get up hours before dawn to wait for their transport, often in freezing cold weather, and endure a long commute to work and back.

Today, more than 20 years since democracy was established, Soweto has been transformed. It has a fully-functioning upper, middle and lower social class with an eclectic mix of modern development and bottom-end housing and trading stores; well-lit roads are lined with trees and there are many attractive green belts that stand out in stark contrast to its former dusty and ugly days.

Informal trading markets are still part of the character of Soweto but its residents now enjoy the luxuries of first-world shopping centres, entertainment facilities, hospitals and schools.

The growth and development of the south-west townships

The Black migrants organised themselves during the James Sofasonke Mpanza’s Squatters Movement of 1944. Informal settlements sprang up to meet the growing lack of housing in the area and people were forced to occupy vacant land.

The townships grew up on the former farms of Doornkop, Klipriviersoog, Diepkloof, Klipspruit, and Vogelstruisfontein. Collectively these settlements were referred to as the South West Townships by the disgruntled apartheid regime, and later renamed Soweto.

Soweto became an independent municipality in 1983. It shifted from being governed by the Johannesburg city council to electing its own Black councillors, in line with the Black Local Authorities Act that was passed by the apartheid government.

This Act was extremely unpopular as Soweto’s newly-established independence did not come with adequate financial resources to address housing and infrastructure issues.

Residents were still forced to commute long distances to their workplaces because, under the apartheid-era laws, formal employment was not allowed within the various townships. Informal markets sprung up and the wives and children of the traditional labour force could supplement their meagre earnings as street vendors while the menfolk laboured at the mines and industrial parks.

The stirrings of discontent

Black citizens of South Africa suffered deeply under the cruel apartheid system but it was discontentment with the education of Blacks that finally led to the tumultuous period of unrest and riots.

The National Party provided limited or no resources to the education of Black youths. In 1953, five years after the came into power, the Buntu education project was established by the Department of Native Affairs as an apartheid platform.

Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, then the Minister of Native Affairs and later Prime Minister, noted at the time that the Buntu education policy was designed to educate Black people to know their place in society; saying, “Natives must be taught from an early age that equality with Europeans [Whites] is not for them.”

Bantu education did provide more education for more Black people than the previous Afrikaans governments had provided but the facilities were meagre and classrooms were overcrowded. No new high schools were built in Soweto between 1962 and 1971 and students were expected to move to their homelands to attend the newly built schools there.

In 1972, the government heeded business calls for a better-trained workforce and built 40 new schools in Soweto. Over the next four years, the numbers of pupils attending high school in Soweto tripled. In 1976, more than 250 000 pupils enrolled in Form one (first year of high school) but there was only space 38 000 across the number of schools in Soweto.

Bantu education was significantly inferior to the education in schools for Whites. The government spent R644 a year on a White child’s education and only R42 on a Black child.

The Soweto Uprising

Relations between the apartheid government and the Black communities of Soweto eventually came to a head in 1976 when the government passed a ruling that Black children must be taught in Afrikaans in schools (the language of the ruling party). This sparked a series of riots that were violently suppressed by the apartheid-ruled police and army.

Rioting was contained for a period of time under military rule but flared up again in 1985 and continued until the first multiracial elections were held in April 1994.

Tensions had been growing from February 1976 when two teachers at the Meadowlands Tswana School Board were dismissed for refusing to teach in Afrikaans. The African Teachers’ Association of South Africa presented a memorandum to this effect to the Education Department. From mid-May around a dozen schools went on strike, and several students refused to write mid-year exams.

On 16 June, students from three schools – Belle Higher Primary, Phefeni Junior Secondary and Morris Isaacson High – organised a march that took them from their schools to the Orlando Stadium where they planned to hold a meeting. However, their peaceful march was intercepted by the state police on Moema Street and the situation turned ugly.

The protest march was organised by the older school children to protest over the enforced ruling of Afrikaans and English as a dual medium of instruction in African secondary schools. Scholars were being forced to write certain exams in Afrikaans despite having no or a rudimentary grasp on the language.

That day and the tragedy that unfolded will forever be captured by a simple photography taken by a young photo-journalist that had been sent by his newspaper, The World, to cover the protest action.

Hector Pieterson (1963-1976; 13 years old) became an iconic symbol of the Soweto Uprising when Sam Nzima captured the image of the dying child being carried in the arms of a young man with his older sister running alongside him. The image was published around the world and bought the plight of the children of Soweto to the world’s attention.

Hector was killed when the apartheid-regime police opened fire on a group of protesting scholars. The pupils had started the day in a peacefully manner but the crowd soon became aggressive and started throwing stones at the police. The crowd grew to the size of about 10 000 rioting pupils, two West Rand Administration officials were killed and a number of vehicles and buildings were set alight.

Outside Phefeni Junior Secondary School a group of about 30 pupils had gathered, singing the traditional Sotho anthem (Morena boloka sechaba sa heso) which was banned at the time under apartheid rule. When the police arrived to contain the protestors, the crowd grew violent and hurled rocks at the police. The police returned fire with tear gas to disperse them. The facts are not clear and no-one knows for sure who gave the order to shoot, but soon children were running in all directions and a few lay wounded on the road.

A young boy by the name of Hastings Ndlovu was the first child to be shot and killed but there were no photographers on the scene at the time and his name is not widely known. When Hector was shot, he fell on the corner of Moema and Vilakazi Street. He was picked up by an 18-year old boy, Mbuyisa Makhubo who, together with Hector’s sister, Antoinette, ran towards Sam Nzima’s car.

Hector was bundled in the car and a journalist, Sophie Tema, drove him to a nearby clinic where he was pronounced dead. Hector and Hastings Ndlovu were buried at the Avalon Cemetery in Soweto and both the cemetery and place where Hector fell has since become a significant landmark commemorating the struggle and bravery of the young children caught up in the Soweto uprising.

The photograph Sam Nzima took of a dying Hector in the arms of Mbuyisa came to represent the anger and tragedy of a day that started out peacefully. It sparked months of clashes between the police, school children and adult protestors. Nzima said years later that the photograph ruined his life as he suffered the consequences of it for many years after, although he realised what significance his quick-thinking actions had on South Africa’s history.

He described the tragedy and his reaction as simply a spontaneous moment in his photo-journalist career. “I saw a child fall down. Under a shower of bullets I rushed forward and went for the picture. It had been a peaceful march; the children were told to disperse, they started singing Nkosi Sikelele. The police were ordered to shoot,” he recalls. “I was the only photographer there at the time. The other photographers came when they heard the shots.”

A few months after the fatal shooting of Hector and the other school children and the publishing of the iconic photographer, the newspaper that Nzimi worked for – The Bantu World – was banned by the apartheid government.

16 June 1976 was a turning point in South Africa’s history and has since been proclaimed National Youth Day and is an annual public holiday. It is a significant day when the people of South Africa remember this time tumultuous time and celebrate the lives of their youth.

A sister’s memory of death

Antoinette Sithole, Hector’s older sister and one of five sisters, still lives in Soweto. She was 17 in June 1976. She remembers that day as if it was yesterday:

“On the day, I was hiding in the second house next to my school Phefeni High School. There were younger children at the march who shouldn’t have been there. I don’t know why they were there – Hector was one of them. There were random shots; we were not familiar with teargas shots. I was confused; those first shots could have been teargas.

“I came out of hiding and saw Hector and I called him to me. He was looking around as I called his name, trying to see who was calling him. I waved at him; he saw me and came over to me. I asked him what he was doing here, we looked around, there was a shot, and I ran back to my hiding place. When I looked out I couldn’t see Hector. I waited, I was afraid, where was he?

“Then I saw a group of boys struggling. This gentleman came from nowhere, lifted a body, and I saw the front part of the shoe which I recognised as Hector’s. This man started to run with the body. I ran alongside and said to him, “Who are you, this is my brother?

“A car stopped in front of us, a lady got out and said she was from the press, and offered us a lift to the clinic. We put him in the car. I don’t remember how I got to the clinic, but the doctor said Hector was dead so I gave his details.

“I was so scared of how I was going to tell my mother. Two teachers from a nearby school took me to my grandmother’s house. A neighbour phoned my mother at work, and when she got home at 5.30pm my uncle was standing outside the house with me. She said she had heard on the radio that children had died. My uncle broke the news – she was calm, she showed no emotion.

“My father lived in Alexandra – my parents are divorced – he saw the picture in the paper and recognised me and wondered why I wasn’t at school. My mother’s strength – she was stronger than my father – helped me come to terms with death. I can accept now that we are all going to die.

“My mother is still alive and still very strong. She still lives in the same house in Soweto. Hector was her only son, and since the uprising she has lost one of my younger sisters in a car accident. To me and my family, Hector did not die in vain.”

What became of the chief protagonists of 16 June 1976?

The legendary photographer, Sam Nzima, left Johannesburg and holed up in the Limpopo province as his life was under threat. After his photograph was published, he was told by the security branch to report to the infamous John Vorster Square (police barracks) but, fearing the worst, he went into hiding instead.

Nzima earned an income from a bottle store he set up and later served as a Member of Parliament in the Gazankulu homeland. He opened a school of photography in Bushbuckridge (now Mpumalanga) after The Sowetan newspaper provided him with a black and white enlarger.

Nzima was only given copyright of his famous photograph in 1999 when the Independent Group bought the Argus newspaper.

Theuns ‘Rooi Rus’ Swanepoel was the police commander in charge on that fateful day and is accused of giving the command to open fire on the schoolchildren. In the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Rooi Rus was described as a policeman with ‘a long history of human rights violations as chief interrogator of the security branch.

Rooi Rus showed little remorse over his actions, saying “I made my mark. I let it be known to the rioters I would not tolerate what was happening. I used appropriate force. In Soweto and Alexandra where I operated, that broke the back of the organisers.”

The sequence of events of that day was described in Die Afrikaner (the far-rightwing Herstigte Nationale Party mouthpiece) as follows:

“In the heat of the struggle, (Swanepoel) and his men are called in from leave to stop a mass of seething, threatening youths. The atmosphere is laden and then one of the blacks throws a bottle into the face of the Red Russian (Rooi Rus). A war breaks out as the young men let loose on the seething crowds and the one responsible for throwing the bottle looks like chicken mesh after the automatic machine gun flattens him.”

Swanepoel allegedly lost his right eye during the protest action. He died of a heart attack in 1998 at the age of 71.

Mbuyisa Makhubo, the 18-year old boy who was photographed carrying the unconscious Hector, was badly harassed by the police after the incident and eventually went into exile. His mother, Nombulelo Makhubo, told the TRC that she received a letter from him from Nigeria in 1978, but that she had not heard from him since. She died in 2004.

Antoinette Sithole, Hector’s sister, was 17 years old when her brother was fatally wounded in the Soweto Uprising. She still lives in Soweto and is actively involved in the management of the Hector Pieterson’s Museum and gives guided tours.

In the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising

In the Hector Pieterson Museum, one of the few walled-in rooms contains the Death Register. This is a record of the names of the children who died over the period from June 1976 to the end of 1977. The day, however, had positive consequences and Hector’s family are reassured that his death was not in vain.

Thousands of scholars joined the broader liberation movement and increased the strength of resistance against the apartheid regime. International solidarity movements garnered support and placed increasing pressure on the apartheid government to change discriminatory laws and regulations.

The state education department relented on Afrikaans being the medium of instruction and more schools and teacher training colleges were built in Soweto. Teachers received better training and resources, and their qualifications were upgraded through state-sponsored study grants.

Most importantly, urban Blacks were finally awarded permanent resident status in South Africa as opposed to being considered ‘temporary residents’ of the designated homelands and inferior townships that were located far from the economic hubs.

On 9 August 2002, US lawyer Ed Fagan represented apartheid-era victims in a US$50 billion class action suit against international firms and banks that profited from dealings with the Apartheid regime. One of the plaintiffs was Dorothy Molefi, Hector’s mother.

The new democratic South African government aswell as Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki and Desmond Tutu chose to distance themselves from the lawsuit and it was famously thrown out of court in 2004.

Soweto today

The status of Soweto was finally recognised in the new democratic era in the late 1990s and the city ballooned in size in the ensuing years. With a significant boost in financial resources, the Soweto landscape has changed from poor, cramped shanty townships to a pleasant suburbia environment that is home to a diverse mix of people.

Soweto’s population is predominantly African Black. All eleven of the country’s official languages are spoken, and the main linguistic groups (in descending order of size) are Zulu, Sotho, Tswana, Venda, and Tsonga.

Houses have been refurbished and new ones built according to the Presidency’s Twenty Year Review and water, electricity and sanitation projects that were neglected during the apartheid era have been completed. Roads have been resurfaced or tarred and most are lined with streetlights. Children and commuters can walk safely on pedestrian kerbs or cycle along a linked cycleway. Heavy rainfall is captured in a comprehensive stormwater system.

Soweto also boasts having Africa’s largest healthcare facility, Chris Hani Baragwaneth Hospital, and five new state-of-the-art shopping malls with major retail anchor tenants. All these modern facilities aswell as its rich historical heritage attracts over 1-million tourists to the city every year. People from around the world are offered an opportunity to visit historic landmarks aswell as enjoy the cultural delights of this uniquely South African metropolitan renaissance.

Although many of Soweto’s residents are poor, collectively they have immense buying power of more than R4 billion. Johannesburg City Council has invested heavily in Soweto, providing more infrastructure such as street lights and paved roads, and shopping centres and entertainment complexes.

Soweto’s most famous street

Vilakazi Street Precinct is now one of South Africa’s most famous streets and the only one in the world to have housed two Nobel Peace Prize winners. It is a popular tourist destination with street art, memorials and benches adorning this historical site.

On a tour to Soweto, visitors can stroll down the street that has been turned into a safe and attractive landmark. Despite the fact that it is a symbol of the city’s struggle history, Vilakazi Street exudes a sense of excitement and hope.

The Vilakazi Street precinct is about a kilometre in length and is bordered by the original apartheid-era houses. The most famous and widely-visited house on the street is the former home of Nelson Mandela, former struggle veteran and President of South Africa. This simple three-bedroomed home is now a museum.

House number 8115 has been restored to what it looked like in 1946 and is now known as Mandela House. Mandela moved in to this house with is first wife, Evelyn Mase. In 1958, he brought his second wife, Winnie, to live in the house with him. He lived in the same house for a brief period of time after his release from prison in February 1990.

A short distance away is Tutu House, the home of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, also a recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize. Two large metal bull heads have been erected outside Mandela’s house, entitled The Nobel Laureates. They stand on the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane Streets and represent the two great men who played such a significant role in the struggle for peace and democracy.

Another metal structure has been placed on Moema Street that depicts this time; of schoolchildren facing a policeman with a growling dog. It was put in place to honour the young children who lost their lives during the student protests of 1976.

A memorial wall of slate has also been erected on the corner of Moema and Vilakazi Streets. It provides visitors with a quiet place to sit and contemplate the fateful day of 1976 and the events that unfolded in its aftermath.

A striking piece of street art is visible where Vilakazi Street intersects with Khumalo Street. Eight huge grey hands spell ‘Vilakazi’ in sign language. These large hands have become play objects that young children enjoy climbing on.

Other murals in the street include one that depicts the scene of 16 June 1976 with police and their vans, and placard-carrying children. Several concrete benches have been livened up with intricate mosaic work and a row of bollards with wooden heads has been placed on the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane streets.

Hastings Ndlovu’s Bridge was erected on the corner of Klipspruit Valley and Khumalo Road in remembrance of the 15-year old boy who was the first pupil shot when the police opened fire on the schoolchildren. He was rushed to hospital but died of his head wound.

There is a statue of the young Hastings on the bridge, dressed in school uniform and standing on a plinth. He is smiling and holding his arm up. Storyboards line each side of the bridge and there is seating that allows visitors a place to sit and contemplate the life of this young boy.

OTHER FAMOUS SOWETO LANDMARKS

A tour of Soweto includes the iconic landmarks that commemorate significant moments in its history. Streets, museums and graveyards tell the silent tale of tragedy, suffering and bravery.

Visitors from around the world may look upon these sights with an impassioned view of its existence but for the people of Soweto these landmarks are a daily reminder of the brave men, women and children who suffered at the hands of a brutal apartheid regime.

The grave of Hector Pieterson at Avalon Cemetery

The press has alternatively spelt Hector’s surname as either Peterson or Pieterson but the family insist that the correct spelling is Pieterson. The family was originally the Pitso family but chose to adopt the Pieterson name to try to pass off as Coloured.

This was a different ethnic group under the Apartheid system of racial classification and a group that enjoyed slightly better privileges under apartheid than Black people did.

The Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum

The memorial site and museum was opened on 16 June 2002 near the place that Hector was shot in Orlando West in Soweto. It not only honours the life of Hector but also those that died on that fateful day and in the months following the 1976 Soweto Uprising.

The Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism awarded R16 million to its development and the Johannesburg City Council contributed an additional R7,2 million to the costs.

The most striking exhibit visitors see shortly after they enter the museum is the blown-up photograph of the dying Hector in the arms of a young 18-year old pupil with his sister running alongside. The photograph is a striking depiction of the agony and suffering of these three young school children. Thereafter, a tour of the Hector Pieterson Museum is a fusion of modern technology and cultural history.

Hector’s sister, now Antoinette Sithole, is often seen at the museum. She gives guided tours and offers an emotional account of that fateful day. Unfortunately you will not see a photograph of Hector as a child as the family do not have a single photo of their famous son. The few photographs that the family had of Hector were handed over to the press with the promise that they would be returned but they never were and the search for them still continues today.

The red-bricked museum was erected in Kumalo Street, two blocks away from where Hector was shot on the corner of Moema and Vilakazi Street. Hector’s mother, Dorothy Molefi, lives in a nearby suburb called Meadowlands. She says the family is very proud of the museum and the fact that children can learn about South Africa’s history there. Hector’s father passed away shortly after the museum was opened but at least he lived to see his son’s memory immortalised in this landmark building.

The museum is a unique design that blends in with the surrounding red-brick, semi-detached houses with iron roof. This was the wish of the community who had a say in its development. A tour of Hector Pieterson’s Museum creates the impression that one is walking through a cathedral, with a double-volume ceiling, tall thin windows, stripped wooden floors, concrete columns and impressively tall walls.

Enlarged black and white photographs are a central theme and visually depict heart-rending scenes of that period. The museum’s curator says the re-representation of the student uprising is an ongoing process and they have been sensitive in depicting the differing accounts of what transpired and how the peaceful protest exploded into a violent clash between the police and crowds.

Regina Mundi Church

This is the largest Roman Catholic Church in South Africa and is found in Rockville, in the middle of Soweto. It is famous for having opened its doors to protesting schoolchildren in 1976 during the Soweto student uprisings.

Protestors sought refuge in Regina Mundi Church as they fled from Orland Stadium under a hail of bullets and blinding teargas. The church was constructed in 1964.

Orlando Towers

The Orlando Power Station is known worldwide as Orlando Towers. It is a decommissioned coal-fired power station that stands out like two sentries overlooking the city of Soweto. The power station was erected at the end of World War II and served the city of Johannesburg for over 50 years.

The mural on Orlando Towers was hand-painted and took 6 months to complete. Orlando Towers has been turned into a distinctive landmark and attracts adventure seekers who come from far and wide to bungee jump off it, swing or freefall their way to the bottom.

Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital

This legendary hospital is the third largest hospital in the world with approximately 3 200 beds for patients. It was built in 1941 by the British Government and served as a military hospital, known then as the Imperial Military Hospital, Baragwanath.

After the war, the Transvaal Provincial Administration bought the hospital for £1 million. On 1 April 1948, the Black section of Johannesburg Hospital (known as Non-European Hospital or NEH) was transferred to Baragwanath Hospital. In 1997 another name change followed, with the extensive facility now known as Chris Hani-Baragwanath Hospital.

Credo Mutwa Cultural Village

Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa (born 1921) was a Zulu sangoma (traditional healer). He was the author of books on stories of traditional Zulu folklore and his own imagined fables. He is best known for the graphic novel he penned called the Tree of Life Trilogy. In addition, he tirelessly campaigned for the research and treatment of the pandemic HIV/AIDS virus and ran a Hospice for Aids patients.

In 1974, Credo obtained a piece of land on the Oppenheimer gardens in Soweto in order to create an African cultural village. He created many sculptures and populated the village with huts and symbols that he claimed was secret African mythology.

Credo believed that the great unrest in Johannesburg and the popularisation of communism in the Black struggle drew Africans away from their traditional roots. Unlike most political activists, he actually supported a separation between White and Black communities in order to preserve Black traditional tribal customs and way of life.

The Credo Mutwa Cultural Village as it is called today has been restored and is open to the public free of charge. Tour guides are available from the caretaker of the village.

Orlando Stadium

This multi-purpose stadium is the home venue for Orlando Pirates Football Club, a professional soccer team that enjoys a massive following among Black soccer fans. The stadium was originally built for the Johannesburg Bantu Football Association and had a seating capacity of 24 000 people.

Orlando Stadium was rebuilt with a modern steel frame and its capacity was increased to 36 761 seats. It gained international recognition in 2010 when South Africa hosted the FIFA World Cup Soccer Tournament. It served as a training centre and hosted the FIFA World Cup Kick-Off Celebration Concert, featuring iconic international artists aswell as South Africa’s own local stars.

FAMOUS TOWNSHIPS

Brickfields

With the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand in the late 1880s, thousands of people of all races and nationalities descended on the region in search of work and riches. To accommodate the arrival of the immigrants and migrant labours, the government bought the south-eastern portion of the farm Braamfontein for a housing settlement.

There were large quantities of clay along the stream that ran through the farm which was perfect for brickmaking. The government issued brickmaker licences which resulted in many landless Dutch-speaking burghers (citizens) settling on the land and making a living from bricks. The area became known as Brickfields.

Other poor working-class citizens; who included Coloureds, Indians and Africans, settled in the area. Wanting to keep race groups separate from each other, the government laid out new suburbs for the Burghers (Whites), Coolies (Indians), Malays (Coloureds) and Kaffirs (Africans). However, the whole area simply stayed multiracial.

Kliptown and Pimville

A bubonic plague scare broke out in 1904 in the shanty town area of Brickfields. The town council decided to condemn. Most of the Black migrant labourers living there were moved far out of town to the farm Klipspruit (later called Pimville), south-west of Johannesburg. The council had erected iron barracks and a few triangular hutments. The rest had to build their own shacks.

The fire brigade then set the 1 600 shacks and shops in Brickfields alight. The area was re-developed as Newtown. Pimville was located next to Kliptown, the oldest Black residential district of Johannesburg and was first laid out in 1891 on land which formed part of Klipspruit farm. The future Soweto was to be laid out on Klipspruit and the adjoining farm called Diepkloof.

Kliptown is the oldest residential area in Soweto and is best known as the site where 3 000 people congregated in 1955 to write the Freedom Charter under the guise of the Congress of the People. It later served as the basis for South Africa’s liberal constitution.

Kliptown Open Air Museum has been developed in the heart of Kliptown and forms part of the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication. This is a historical open-air museum where you will find informal trading markets, restaurants, shops, art galleries and an upmarket hotel.

Orlando, Moroka and Jabavu

In 1923 the Parliament of the Union of South Africa passed the Natives (Urban Areas) Act (Act No. 21 of 1923). The Act provided for improved conditions of residence for natives in urban areas, to control their movement into such areas and to restrict their access to intoxicating liquor.

The Act required local authorities to provide accommodation for Natives (then the polite term for Africans or Blacks) that were lawfully employed and resident in the areas designated to them. The Johannesburg town council formed a Municipal Native Affairs Department in 1927 and bought 1 300 morgen of land on the farm Klipspruit No. 8. The first houses built on this farm in 1930 were part of housing settlement referred to as the Orlando Location.

The township was named after the chairman of the Native Affairs committee, Edwin Orlando Leake.

Orlando West

In 1934 James Sofasonke Mpanza moved to 957 Pheele Street in Orlando Location. A year after his arrival he formed his own political party, the Sofasonke Party, and was very active in the affairs of the Advisory Board for Orlando.

Towards the end of World War II there was an acute shortage of housing for Blacks in Johannesburg and the Sofasonke Party encouraged Blacks to put up their own squatter shacks on vacant municipal land. On 25 March 1944, hundreds of homeless people of Orlando and elsewhere joined Mpanza and marched to a vacant lot in Orlando West and set up a squatter camp.

The City Council’s resistance to the squatter camp dissolved and, after much negotiation, it was agreed that an emergency camp that would house 991 families could be erected. It was to be called Central Western Jabavu.

The next wave of land invasions took place in September 1946. Some 30 000 squatters congregated west of Orlando and shortly thereafter, the City council proclaimed a new emergency camp. It was called Moroka. The camp became Johannesburg’s worst slum area. There was only a communal bucket-system toilets and very few taps with clean, running water. The camps were meant to be used for a maximum of five years but, when they were eventually demolished in 1955, Moroka and Jabavu housed 89 000 people.

FAMOUS RESIDENTS OF SOWETO

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela is most famous for having served 27 years in prison as a struggle activist who resisted and fought against the oppression of Black people under the apartheid. The apartheid system was part of an era when non-White citizens were segregate from White citizens and did not have equal rights.

Mandela was a civil rights activist and leader of the struggle movement who later became President of South Africa for two terms. Mandela was an iconic man who represented the hopes and aspirations of all Black South Africans in a dark and oppressive era. The way Mandela embraced unity and diversity on his release from prison and as President of the country will forever be regarded as his abiding legacy.

Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 in a town called Mvezo. His birth name was Rolihlahla but he was nicknamed Nelson by a teacher in school. He was a member of Thimbu royalty and his father was Chief of the city of Mvezo. He attended school and college at the College of Fort Hare and University of Witwatersrand. He obtained a law degree at Wits and met some of his fellow activists that would later lead the struggle movement.

Mandela became leader of the African National Congress (ANC) and tried to lead the movement according to the non-violent philosophy of Mohandas Gandhi. When this did not work, Mandela established an armed branch of the ANC and initiated the bombing of certain buildings. The intention was only to damage buildings and no one was meant to get hurt.

He was classified as a terrorist by the apartheid government and relentlessly pursued until he was caught and sent to prison. He spent the majority of his prison sentence on Robben Island and suffered terribly, along with his fellow ANC cadres.

Mandela was finally released from prison in 1990 and again took up active leadership of the ANC. He continued to campaign for the end of apartheid and Black oppression and his dedication to the cause resulted in the first independent elections that were held 1994. For the first time in South African history, Black citizens were allowed to cast their vote.

The ANC won the 1994 elections and as head of the organisation, Mandela became President of South Africa. One would expect a man who had suffered so much at the hands of White leadership and severe racial discrimination to be bitter and revengeful but instead he lead with true integrity believing that all South Africans had the right live a free and equally-just life.

Mandela had six children and twenty grandchildren. He passed away on 5 December 2013, leaving behind a momentous legacy. Mandela received over 695 awards for his civil rights and humanitarian efforts but the most notable was the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

Nelson Mandela believed that education is the most powerful weapon that one can use to change the world and that there is no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children. Mandela would have been immensely proud to see the bravery and courage of the young children like Hector and Hastings who died in the Soweto student uprising immortalised in the memorial landmarks and museum in Soweto.

Oliver Reginald Tambo

Oliver Tambo was the leader of the African National Congress and lived in exile for thirty years. He died in 1993 before he could witness the liberation of the Black citizens of South Africa.

Tambo was made of the same cloth as Nelson Mandela. He was thoughtful, wise and warm-hearted and much-loved by his people. He had a nurturing style of leadership and a genuine respect for all people from all walks of life. His vision for the leadership of South Africa was one of inclusion and unity.

He was the founder member and secretary of the ANC Youth League which was established in 1944, and the general secretary of the ANC from 1952; the President of the ANC from 1977 to 1990; and National Chairperson until his death.

Tambo’s politics and leadership were shaped by his traditional rural roots and the knowledge he acquired through education. He sought to empower his struggle cadres and encouraged them to find creative, preferably non-violent approaches to bringing about change.

This great leader stood firm on the necessity for a multi-party democracy after liberation in which there would be freedom of speech, of assembly, of association, of language and religion. This was the alternative to the one-party state model adopted by so many independent and failing African countries.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (born 1931) is an iconic figure in South African history who is a well-known social rights activist and the first Black Archbishop of Cape Town and Bishop of the Church of the Province of southern Africa. He was a fierce opponent of apartheid in the 1980s and has campaigned tirelessly on a number of human rights issues. Now retired, he is still a key spokesman for the rights and freedoms of all South Africans.

Tutu has been involved in campaigns to fight the scourge of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and xenophobia. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984; the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism in 1986; the Pacem in Terris Award in 1987; the Sydney Peace Prize in 1999; the Gandhi Peace Prize in 2007;[1] and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. He has also compiled several books of his speeches and sayings.

Growing up Tutu wanted to become a doctor but his family could not afford the tuition and training, so he followed in his father’s footsteps and became a teacher. He resigned from his teaching post during the time the Bantu Education Act was enforced, in protest of the poor educational prospects for Blacks. Tutu went on to study theology and was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1961.

He moved into a house that has since become known as Tutu House, on the same street where Nelson Mandela lived. Tutu and his family lived in this same house for many years, long after South African gained its independence and Blacks were free to live where they chose.

Tutu took on the position of Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches. In this role he was able to his work against apartheid with support of nearly all the churches. Through his writings and lectures at home and abroad, Tutu consistently advocated reconciliation between all parties involved in apartheid. Tutu’s opposition to apartheid was vigorous and unequivocal, and he was outspoken both in South Africa and abroad.

Tutu was also instrumental in the development and changes to South Africa’s constitution and, when South Africa gained its independence and the apartheid system was abolished, Tutu headed up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Nelson Mandela noted that Tutu had made an “immeasurable contribution to our nation”, described him as “sometimes strident, often tender, never afraid and seldom without humour; Desmond Tutu’s voice will always be the voice of the voiceless”.

Tutu famously coined the phrase Rainbow Nation that is now widely used as a metaphor to describe the ethnic and cultural diversity of the country.

Although Tutu is retired, he is a stalwart of the ANC party and one of their biggest critics in these tumultuous political times. He has been vocal in his condemnation of corruption, the ineffectiveness of the ANC-led government to deal with poverty, and the outbreaks of xenophobic violence in South Africa.

Teboho MacDonald Mashinini

Teboho “Tsietsi” MacDonald Mashinini (1957-1990) lived in Central Western Jabavu. He was the primary student leader of the Soweto Uprising that began in Soweto and spread across South Africa in June 1976.

Tsietsi was a bright, popular and successful student at Morris Isaacson High School in Soweto where he was the head of the debate team and president of the Methodist Youth Guild. He planned a mass demonstration by students to protest a move by the apartheid government to make Afrikaans a mandatory language of education. His planned protest march led to the Soweto Uprising that lasted three days during with several hundred people were killed, of which the majority were Black school-going children.

Under threat of prosecution, Tsietsi fled South Africa and lived in exile – first in London and later in various African countries. He died under mysterious circumstances and his body was repatriated to South Africa where he was laid to rest in Avalon Cemetery. His grave bears the epitaph “Black Power”.

There is a statue of Teboho Mashinini by Johannes Phokela in the grounds of his old school that was unveiled in May 2010.

Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

The current Deputy President of South Africa is a politician, businessman, activist and trade union leader. Ramaphosa (born 1952) grew up in Soweto but was sent to a rural boarding school to complete his college education.

Ramaphosa has led an active life in both politics and business, and was Nelson Mandela’s preferred choice as future president. He is a skilful negotiator and strategist, and built up the biggest and most powerful trade union in South Africa – the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

He played a crucial role, together with Roelf Meyer in the National Party, during the negotiations to bring about a peaceful end to apartheid and steer the country towards its first democratic elections in April 1994.

Ramaphosa is known to be one of the richest people in South Africa with an estimated net worth of $450 million.

Mosima Gabriel “Tokyo” Sexwale

Sexwale (born 1953) is a formidable businessman, politician, anti-apartheid activist and former political prisoner. He was given the nickname Tokyo because of his childhood love of karate. He was born in Orlando West and was part of the generation of young men and women who fought against apartheid rule and oppression.

As a young man, he joined the African National Congress’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (“spear of the nation”). In 1975, Sexwale went into exile, undergoing military officers’ training in the Soviet Union, where he specialised in military engineering.

When he returned to South Africa in 1976, Sexwale was captured after a skirmish with the South African security forces and, along with 11 others, was charged and later convicted of terrorism and conspiracy to overthrow the government after an almost two-year-long trial in the Supreme Court of South Africa in Pretoria. Sexwale was sent to the Robben Island maximum-security prison to serve an 18-year sentence.

While incarcerated at Robben Island, he studied for a BCom degree at the University of South Africa. He spent 13 years in prison and was finally released in 1990. When Nelson Mandela was elected President of South Africa, he made Sexwale Premier of Gauteng province.

Sexwale left politics for business and made an extreme fortune as a major oil and diamond mining magnate. He still had aspirations of becoming President of the country and made an unsuccessful bid in 2007, losing out to Thabo Mbeki. In 2009, he was appointed as Minister of Human Settlements by President Zuma.

In 2009, Zuma appointed Sexwale as Minister of Human Settlements, but it was no secret that Sexwale still had presidential aspirations. Relations soured with Zuma and in 2013 Sexwale found himself out in the cold in a cabinet re-shuffle.

REMENANTS OF A BY-GONE ERA

The majority of houses in Soweto are the typical old “matchbox” houses or four-room square houses that were built by the former government. This was cheap accommodation built for the migrant work force. Large homes have been built more recently that are similar in stature to those in the more affluent suburbs of Johannesburg.

People who still live in the old “matchbox’ houses have improved and expanded their homes, and the City Council has planted trees and created green belts in the common areas. Informal settlements with shanty huts are dotted around Soweto, reminding one that there are still many Black people living in poverty in Soweto.

Hostels are another prominent physical feature of Soweto. They were originally built to house male migrant workers and many have since been improved as dwellings for couples and families.

THINGS TO DO IN SOWETO

The majority of local and international tourists visit Soweto for its historical heritage and to view the iconic landmarks that shaped its history. However, Soweto has so much to offer than Vilakazi Street Precinct and the houses of the struggle movement veterans.

It is a city that beats to its own tune during the day and comes alive at night.

For adventure seekers

There are a number of businesses in Soweto offering experiences for adrenalin junkies but the most popular attraction is bungee jumping, swinging or free-falling from the Orlando Towers.

Safely ensconced in a tight harness, an open-air lift transports you up the outside of the tower to a platform three metres from the top. A quick walk along the floating staircase takes you to the tower’s rim and to either the sky-bridge (between the two towers) for the bungee or the platform for the swing.

The Soweto Bungee Jump is a fall from a height of about 33 storeys and the Power Swing is a 40 metre freefall before the swing cables kick in. Ominously named Abyss and another world-first experience, is a bungee jump inside the tower and a full swing across the width of its base. There is a viewing platform for the slightly less adventurous.

For artists and cultural fundis

Soweto is adorned with street art and mural paintings depicting the struggle, pain and bravery of its people.

The Orlando Towers are most famous as a visual feast of artistic imagery. The one tower is painted with various murals that highlight South Africa’s diverse culture. Images include the world-famous Soweto String Quartet; typical suburban houses in the township of Soweto; local barters selling fresh produce; and the iconic Nelson Mandela, who was instrumental in ending the Apartheid era.

Vibrant street art tell the story of Soweto and mosaic creations have transformed the grey, lifeless concrete benches that are provided for those visiting historical sights. The artwork is said to have created connectedness where once only division existed. It has created renewed hope for a positive future, despite a harrowing past. This street art now serves as a constant reminder that vision, determination and creativity are able to create a masterpiece in even the most unlikely settings.

For those who shop until they drop

Informal trading and craft markets are still central to the character of Soweto. Some are geared for the tourists while the balance is hawkers and vendors going about their daily lives, earning a subsistence living to provide for their families.

Five modern shopping malls have been developed since the dawn of democracy and offer visitors and residents hours of enjoyment where friends and family can shop, socialise eat out or just browse. The two most popular shopping malls are:

Jabulani Mall:

Situated in the heart of Soweto, Jabulani Mall opened its doors in 2006 and is affectionately known as the People’s mall. It has a few national anchor tenants and a wide variety of stores selling international and local brands. Its food court is hugely popular and its shiny, clean interior excludes an upmarket, classy sense of style.

Maponya Mall:

This impressive shopping centre was the brainchild of Richard Maponya and was opened by President Nelson Mandela in 2007. Maponya created a mall that mirrored the soul of Soweto. Situated in the heart of Kliptown, the mall is centrally located to the surrounding suburbs. Its unique design features court areas, exhibition facilities and a diverse selection of take-away outlets and restaurants.

For festival goers

The Soweto Wine Festival was started in 2004 and is a 3-day affair that today attracts more than 6 000 wine enthusiasts to the city and over 100 of South Africa’s finest wineries. The festival now includes exhibitions showcasing local travel destinations, trends in local and international cuisine aswell as artists, crafters, fashion designers and leading lifestyle brands. The annual event is usually hosted in March.

For outdoor enthusiasts

If you have a few hours to spend idly exploring the sights of Soweto, visit Dorothy Nembe Park. This is a 26-hectare green belt that is home to unusual sculpted figurines that stand four to five times then the height of a man, with their arms outstretched and trees planted behind them.

The green belt was named after Dorothy Nembe (1931-1998) who was one of the struggle heroines. She was a political activist and Women’s Rights campaigner, and received a prestigious award from the United Nations for her efforts in the fight against oppression. Dorothy most famously led a Natal contingent of women to the Union Buildings in 1956 to protest against the introduction of passes for women.

Dorothy worked alongside Albert Luthuli, Moses Mbhida, Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo after being recruited by Umkhonto we Sizwe and was instrumental in organising women in rural areas in anti-government demonstrations – a campaign known as the Natal Women’s Revolt. She spent 18 years in prison for her part in the resistance.

The park includes a bird hide overlooking a series of dams, an environmental centre, a children’s play area, sporting facilities and a dam. Other features include a new golf driving range, pedestrian walkways, bridges, soccer pitches and braai and picnic areas. There is also a plant nursery that is part of a project that experiments with using ‘hydro seedlings’ – a way of planting that involves a combination of mulch and seed sprayed together over prepared ground.

It takes about 30 to 45 minutes to walk around the park.

For runners

The Old Mutual Soweto Marathon honours the rich heritage of Soweto by taking runners past the iconic landmarks of the area. Runners pass six significant heritage sites one the marathon route, including Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Walter Sisulu Square, Regina Mundi Catholic Church, Morris Isaacson High School, Vilakazi Street and the Hector Pieterson Memorial.

The Old Mutual Soweto Marathon encourages South Africans to learn more about the rich heritage of Soweto, and also exposes international runners to one of the most vibrant and historically significant parts of the country.

Dubbed “The People’s Race”, the Soweto Marathon has a special place in the hearts of many South African runners.

EATING OUT IN SOWETO

There are a number of great restaurants in Soweto that offer visitors a finer dining experience but Moafrika Tours will introduce you to informal eateries that serve authentic African dishes for a unique cultural experience.

Do not miss an opportunity to try a dish called “walkie talkie” – chicken feet and heads served with a delicious relish and pap (mielie meal). Your Moafrika Tours guide will take you to one of the many taverns or roadside food stalls where food is cooked over open fires and served with traditional side dishes.

Wandies Place in Dube

This tavern-style eatery was the first township restaurant to attract foreign visitors and it is now a popular tourist destination. Service is super-friendly and there is a good selection of township cuisine featuring the likes of ting (fermented sorghum) and umleqwa chicken stew.

Restaurant Vilakazi

This restaurant is located in the famous Vilakazi Street Precinct. You may be subjected to queues of tourists as it is close to Mandela and Tutu House but it is well worth a visit. It serves what can be described as “South African fusion” food where traditional cuisine is given a modern twist. It has a fully stocked bar and is a hugely popular hangout in the evenings.

The most popular dish is their oxtail stew, followed by their mogodu and samp dish served with traditionally-prepared butternut and spinach. It is a more classy establishment than the local taverns but the atmosphere is relaxed and the prices are very reasonable.

Nexdor

This restaurant offers uncomplicated, simple but good quality food. It is located in the heart of Vilakazi Street Precinct and another popular tourist destination. The most popular dish is their steak sandwich that is served with a fried egg on top and a large portion of fries. Nexdor is open until late in the evening and is a popular nightspot for locals.

Nsitsi’s Fun Food

This is a simple street stall but one of the most famous eateries in Soweto. Located in Diepkloof on Eben Cuyler Drive, it is renowned for serving the best Soweto-style kotas which is a township version of bunny chow. Sometimes called a township burger, a kota is a quarter loaf of bread that is hollowed out and filled with potato fries, a Russian sausage, cold meats, cheese, mango atchar and your choice of sauce.

Ntsitsi has 40 variations of kotas and people drive from central Johannesburg to try out different dishes as one visit is never enough.

Chaf Pozi

This restaurant is located directly below the Orlando Towers and a hugely popular tourist destination in Soweto. It’s the perfect spot for a delicious meal to finish off an adrenalin-filled morning bungee jumping from the towers. The restaurant is decorated to mimic a Soweto-style shebeen which gives it an authentic African vibe.

It is known as a chesa nyama spot where you choose your cut of meat from the butcher window and then wait for it to be cooked on an outside braai (barbeque). You can choose any popular side dish from pap to chakalaka, coleslaw, spinach and butternut. Lashings of gravy or relish make it a mouth-watering meal.

The Jazz Maniacs and Rusty’s Bar at the Soweto Hotel

Soweto has a four-star hotel situated at the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication in Klipspruit which boasts a fancy restaurant, bar and conference centre. Their food is a fusion of traditional African cuisine and modern western cuisine with contemporary plating.

Visitors can choose what they want to eat for a food buffet packed with uniquely-South African dishes. The hotel allows walk-ins and their food prices are very reasonable.

Tavern

This restaurant is situated in Maponyane Mall and has a loyal following of die-hard fans. Tavern has embraced the tried and tested recipes of African cuisine but has given them a modern twist. An example of this is the Township breakfast that includes ox liver and tomato relish.

Tavern is a popular nightspot and hosts comedy evenings, Jazz nights and Ladies’ nights on different evenings. It is quieter during the day but gets very busy in the evenings.

Sowetalian

The owner of Sowetalian has an Italian father and a Sotho mother, and grew up in Lesotho. It’s obviously then that the food they serve is a fusion of typical township food and authentic Italian dishes. Traditional pasta dishes are served with beef liver; pizzas and bruschetta are topped with interesting toppings made from local African ingredients.

Chef and co-owner Paula has an Italian dad and a Sotho mom and grew up in Lesotho. At Sowetalian, she and her husband have taken typical township food and fused it with authentic Italian cooking. Think pastas with beef liver, pizzas topped with interesting toppings, and bruschetta topped in interesting ways.

Vuyos Restaurant

This restaurant is housed in a beautiful glass building and is famous for serving dishes cooked in an iron cauldron on an open fire. Popular dishes include lamb or vegetal potjiekos (stews) and the Vuyokazi Family platter.

Other favourites are their idombolo (dumplings), pork ribs, a grilled half-chicken and chips, zim-zim balls (a crunch Zimbabwean snack) and mogodu (tripe). Side dishes usually include a selection of morogo (wild leaves like spinach), chakalaka, umgqusho and pap.

Shebeens

Soweto shebeen tours are a unique way to experience the culture and friendliness of the people of Soweto. During the apartheid era, shebeens sprung up and served as meeting places for those involved in the struggle movement.

A number of shebeens in Soweto serve traditional African beer called “Umqombothi” made from fermented yeast. Something one should try while enjoying a delicious meal of “walkie talkies”.

THE BIRTHPLACE OF KWAITO AND KASI RAP

Kwaito and Kasi rap are styles of hip-hop music that are unique to South Africa. The music is a blend of house, American hip-hop and rap with traditional African styles of music thrown into the mix. This unique genre of music has become popular among Black South Africans and many international artists have tried to replicate its unique sound.

GETTING THERE

The M70 is known as the Soweto Highway and links the city with central Johannesburg. Otherwise Soweto is reached taking the N1 Western Bypass that skirts the eastern boundary of Soweto.

The highway is multi-laned, with dedicated lanes for mini-buses and large buses. Mini buses (taxis) are the most popular mode of transport for commuters and it is estimated more than 2 000 mini-buses operate out of the Baragwanath taxi rank alone.

For many years PUTCO provided bus commuter services to Soweto residents but now there is also a rapid bus transit system Rea Vaya that provides transport for around 16 000 commuters daily.